The Golden Age of German Film

WWI brought a new agenda for the German film industry. With the entry of

the U.S. into the war in 1917, Erich von Ludendorff, Quartermaster General

of the Army, concluded that more drastic measures should be taken to meet the

general wave of anti-Germany propoganda coming from the well-equiped studio

of its new enemy. On December 18, 1917, the German High Command formed

UFA (Universum Film A.G.), which brought together prominent financiers and

industrialists with the largest film companies in Germany. UFA's raison d' être was clearly propogandistic. As noted

by one film historian, "The official mission of UFA was to advertise Germany

according to German directives. These asked not only for direct screen

propoganda, but also for films characteristic of German culture and films

serving the purpose of national education".

UFA's raison d' être was clearly propogandistic. As noted

by one film historian, "The official mission of UFA was to advertise Germany

according to German directives. These asked not only for direct screen

propoganda, but also for films characteristic of German culture and films

serving the purpose of national education".

The intent of UFA was soon realized by Ernst Lubitsch with his production

of Madame Dubarryreleased in 1918. The film achieved a near

revolution in the art of film. Lubitsch did with the camera what no

previous German director had. Upon its release in the U.S. in 1920,

Madame Dubarry, retitled Passion, was acclaimed the most important European

picture since the Italian production of Cabiria. With Madame

Dubarry, Lubitsch emerged as a director of would stature and the German

film achieved its first breakthrough in the international market since the

Armistice.

In 1921, the Reich government divested itself of its UFA holdings, with the

Deutsche Bank acquiring its shares. Reconstituted as a private company, the

primary objective of UFA was to be the production of commercial films of high

artistic value that would be capable of competing on the world market,

especially the American.

Germany was in poor shape by the end of WWI. Many citizens were dying of starvation

as the country was faced with high inflation and widespread unemployment.

The anguish of the period was reflected in Fritz Lang's two-part film,

Dr. Mabuse der Spieler (Dr. Mabuse the Gambler), released in 1922. The

film depicts an unscrupulous criminal who gambles with lives and fortunes.

The Aufklärungsfilme "films about the facts of life" emerged during

this period. Most of these films were actually sex films, only thinly

veiled as education. Popular demonstrations and legal action against the

Aufklärungsfilme occured throughout Germany. The National Assembly

proposed the nationalization of the film industry which was rejected in

favor of a National Censorship Law, adopted in May, 1920. Under this law

children under twelve were prohibited from seeing films while children

between twelve and eighteen could only be admitted to films which had

been designated with a special certificate. No film could be prohibited due

to its content.

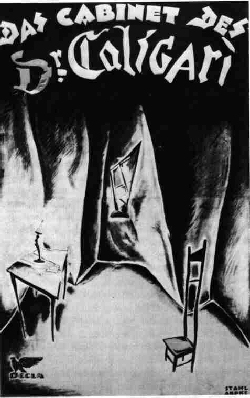

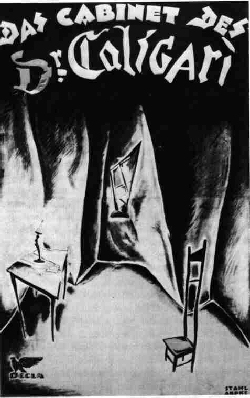

The most enduring of the films of the 1920's are those that came out of the

expressionist movement. As an artistic movement, German expressionism

antedated WWI. Film, the newest of the arts, was also the last to reflect

expressionism. Two definitive expressionist films are Das Kabinett des Dr.

Caligari (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari), directed by Dr. Robert Weine in

1919-20, and Metropolis, directed by Fritz Lang in 1926-27.

. Das Kabinett des Dr. Caligari, based on a

story by Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz, suggests the darker aspect of expressionism

with its probing of insanity. The authors originally intended for the film

to serve as an allegory against insane authority as represented by the tyranny

of Dr. Caligari, but the film ends with the harmless doctor telling his piers

that he can cure his patient now that he understands the root of his own

psychosis.

. Das Kabinett des Dr. Caligari, based on a

story by Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz, suggests the darker aspect of expressionism

with its probing of insanity. The authors originally intended for the film

to serve as an allegory against insane authority as represented by the tyranny

of Dr. Caligari, but the film ends with the harmless doctor telling his piers

that he can cure his patient now that he understands the root of his own

psychosis.

Metropolis, directed by Fritz Lang in 1926, emphasizes the importance of the

spiritual as opposed to the material and the notion that through choas and

destruction a new and better world will come about. The overthrow of the

old order was an essential prerequisite for the coming of the "New Man" and the

establishment of the "Kingdom of Love". The final title reads: "There can

be no understanding between the hand and the brain unless the heart acts as

mediator."

Metropolis, directed by Fritz Lang in 1926, emphasizes the importance of the

spiritual as opposed to the material and the notion that through choas and

destruction a new and better world will come about. The overthrow of the

old order was an essential prerequisite for the coming of the "New Man" and the

establishment of the "Kingdom of Love". The final title reads: "There can

be no understanding between the hand and the brain unless the heart acts as

mediator."

The pure expressionism of Das Kabinett des Dr. Caligari and

Metropolis, although among the most famous of German films from the 20s,

was not characteristic of the several thousand motion pictures produced between

1919 and the end of the silent era. Although both were artistic and remain

the quintessential examples of cinematic expressionism, neither Das Kabinett

des Dr. Caligari nor Metropolis were commercial successes. And

while the German film achieved an international renown for the artistry of

selected motion pictures, the industry never rested on a firm financial basis.

This struggle between artistic expression and financial succuss would plague

the German cinema for years to come.

For some German filmmakers, success was measured by American popularity. Ernst

Lubitsch was the first of the major German directors to accept an American

assignment. He was asked by Mary Pickford (a popular American actress of the

20s) to direct Rosita. Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau's Der letze Mann

earned him an invitation to direct American films. Murnau's American work

consists of only four films: Sunrise (1927), The Four Devils

(1928), City Girl (1930), andTabu (1931). After completion of

Tabu, Murnau died in an automobile accident near Santa Barbara, California.

Besides Lubitsch and Murnau, many other German directors and actors entered

the American industy during the 20s, a trend that continues today.

Fritz Lang, director of Der müde Tod, Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler and

Die Nibelungen, was the principle German director to remain outside

the American industry during this first wave of immigration. Lang had no

desire to move to Hollywood. While visiting America, Lang told an interviewer

that while he admired the technical resources of the American industry, he

found American directors too commercial and less devoted to art than their

German counterparts. Lang clearly had a different idea regarding the potential of

film than did the American directors of the time.

Back to Homepage

The Formative Years

Third Reich Films

Post WWII Films

Emergence of the "New German Cinema"

Related Links

UFA's raison d' être was clearly propogandistic. As noted

by one film historian, "The official mission of UFA was to advertise Germany

according to German directives. These asked not only for direct screen

propoganda, but also for films characteristic of German culture and films

serving the purpose of national education".

UFA's raison d' être was clearly propogandistic. As noted

by one film historian, "The official mission of UFA was to advertise Germany

according to German directives. These asked not only for direct screen

propoganda, but also for films characteristic of German culture and films

serving the purpose of national education".

. Das Kabinett des Dr. Caligari, based on a

story by Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz, suggests the darker aspect of expressionism

with its probing of insanity. The authors originally intended for the film

to serve as an allegory against insane authority as represented by the tyranny

of Dr. Caligari, but the film ends with the harmless doctor telling his piers

that he can cure his patient now that he understands the root of his own

psychosis.

. Das Kabinett des Dr. Caligari, based on a

story by Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz, suggests the darker aspect of expressionism

with its probing of insanity. The authors originally intended for the film

to serve as an allegory against insane authority as represented by the tyranny

of Dr. Caligari, but the film ends with the harmless doctor telling his piers

that he can cure his patient now that he understands the root of his own

psychosis.

Metropolis, directed by Fritz Lang in 1926, emphasizes the importance of the

spiritual as opposed to the material and the notion that through choas and

destruction a new and better world will come about. The overthrow of the

old order was an essential prerequisite for the coming of the "New Man" and the

establishment of the "Kingdom of Love". The final title reads: "There can

be no understanding between the hand and the brain unless the heart acts as

mediator."

Metropolis, directed by Fritz Lang in 1926, emphasizes the importance of the

spiritual as opposed to the material and the notion that through choas and

destruction a new and better world will come about. The overthrow of the

old order was an essential prerequisite for the coming of the "New Man" and the

establishment of the "Kingdom of Love". The final title reads: "There can

be no understanding between the hand and the brain unless the heart acts as

mediator."